Moderators and Panelists

Selection

Like the candidates, the role of moderators and panelists are central to the success of a debate. Moderators manage the debate and ensure that the candidates follow the mutually agreed upon rules, especially time limits. Panelists, who are often journalists, ask questions of the candidates. Depending on the format of the debate, these roles can be separate or combined.

In selecting a moderator, several criteria are recommended:1

- Politically Neutral – The moderator should be someone seen as impartial by the public and the candidates to avoid any perceptions of bias;

- Knowledgeable of Election Issues – If the debate format has the moderator asking debaters questions, he or she should be well-versed in the candidates’ background and the top campaign issues;

- Profile – While sponsors will likely want to select a known and respected figure to moderate, it is advisable to avoid a media “celebrity” who could potentially compete with the debaters for the attention of the audience and distract from the substance of the debate.

- At the same time, the ideal moderator needs to have sufficient stature and experience to manage the conduct of the debate effectively, including holding candidates to the rules in a respectful but firm manner. Including moderators or panelists who provide gender balance over a series of debates can also send a positive message of inclusion; and

- On-Air Expertise – Moderating a debate is often a high stress endeavor. Managing a fast-moving debate while dealing with the pressures of a live radio or television broadcast can be difficult. Selecting moderators with previous on-air experience can help ensure they are able to manage the debate and related production issues, including the use of an IFB earpiece.

The best role for the moderator is not to have one

Ricardo Boechat, Principal Anchor, Jornal da Band of TV Bandeirantes and national radio anchor for BandNews FM; Moderator, Bandeirantes presidential debates.2

The moderator should be the frame not the picture

Patrick Semphere, Moderator, Presidential Debate Task Force of Malawi3

The role of moderator is the most difficult challenge I faced in 54 years as a journalist.

Jim Lehrer, 11-time moderator of U.S. general election presidential debates and executive editor at the Public Broadcasting System

It’s the candidates’ debate – they are running for president; [voters] are not electing a moderator.

Bob Schieffer, three-time moderator of U.S. general election presidential debates and chief Washington correspondent for CBS News4

Preparations

In preparing for debates, sponsors may wish to work with panelists and moderators on the following issues.

Know the Debate Rules

The sponsors must be certain that the moderator and panelists are intimately familiar with the debate rules, including the format, time limits and specific terms negotiated with the candidates, such as how candidates will be addressed and the order of speaking. Having well briefed moderators and panelists helps ensure the debate runs smoothly on air and averts possible candidate complaints that the sponsor is biased, which can be used as a rationale to skip future debates.

Develop Concise, Easily Understood Questions

Since the overall goal of the debate is to inform everyday voters, the questions developed by debate sponsors, panelists or citizens should be brief and straightforward. It is important to avoid esoteric questions that may be perceived as serving mainly to showcase a questioner’s knowledge and expertise rather than assist the voter in choosing among candidates. This includes avoiding long preambles that take time away from the candidates. Questions containing multiple parts enable candidates to respond to the portion they prefer. Based on experiences of sponsors in a range of countries, questions of less than 30 seconds are recommended.

The moderator and panelists need to be scrupulously neutral and evenhanded during a debate. Even body language must convey fairness.

Maintain Steadfast Impartiality

As noted, the moderator and panelists need to be scrupulously neutral and evenhanded during a debate. The tone and content of questions and even body language must convey fairness.

Prepare and Coordinate Questions

To help ensure concise, effective questions, many panelists find it helpful to write out questions beforehand. If the debate format involves a number of panelists, it is recommended that they meet privately and discuss the topic areas they wish to cover to avoid duplicative questions. Illustrating questions with statistics or examples can help make them more interesting and impactful. Also, it is recommended that the moderator be prepared with extra questions in the event candidates do not use all of their allotted time, leaving room for more rounds.

Create a Debate “Run Down”

To help manage the debate, a moderator may wish to refer to a minute by minute schedule or “run down” during the forum. This reference document breaks the debate down into its component parts: introduction, questions, answers, rebuttals, discussion and closing statement as well as the time allocated to each segment. The schedule can help the moderator follow the debate format, ensure all candidates are treated equitably and keep the debate to its planned length (see Example: Debate Run Down (Excerpt)).

Rehearse at the Debate Venue

As with the candidates, providing moderators and panelists with the opportunity to visit the debate venue — to run through the format and become comfortable with the staging, timing systems, microphones and cameras — can boost the quality and professionalism of the debate. In addition, sponsors can also work with moderators and panelists to develop a plan for handling incidents that can occur during a debate. Such scenarios may include:

- A candidate repeatedly violates the agreed upon rules of the debate, such as making personal attacks against an opponent or ignoring time limits;

- An audience member disrupts the debate;

- A candidate does not show up (or arrives unexpectedly) for the debate at the last minute; and

- Production problems occur mid-debate including an audio, camera or power failure.

Prepare Remarks

In opening the debate, a moderator may wish to touch on several key points, including reviewing the format and rules as well as providing instructions to the audience on decorum (i.e. turn off cellphones, no applause or other reactions). At the close, the moderator can thank the candidates and promote the dates, times and locations of upcoming debates. (see Example: Moderator Script.)

Candidates and Political Parties

Selection

In organizing debates, sponsors often face the dilemma of how many candidates should be invited. The issue often centers on whether sponsors should be inclusive of all candidates who are running for a particular office, which in some cases could number into the dozens, or focus primarily on aspirants who have a reasonable chance of winning. The decision is often particularly relevant in charged political environments in countries that are emerging from conflict, navigating a democratic transition or confronting regional, ethnic or religious divisions. There are tradeoffs with either of these alternatives that sponsors can weigh.

With an inclusive debate, the sponsor sends the message that all candidates have a right to be heard. At the same time, inviting candidates from minor parties to a debate can, in some instances, cause the leading contenders to drop out. From an organizational perspective, involving all candidates makes staging more cumbersome and reduces the time each candidate has to speak.

Limiting the number of candidates allows voters to hear in more depth about the policies of the front runners, who are more likely to actually gain office and govern. However, excluding a number of candidates can open up sponsors to public accusations of discrimination and political bias against the aspirants (or even legal action) from smaller parties that do not receive an invitation.

When contemplating these tradeoffs, some sponsors opt for a middle ground that incorporates elements of both positions by holding multiple debates or adding complementary activities to help all candidates get their message to the public. These approaches can include the following.

Hold Multiple Debate Sessions

To accommodate a large number of candidates, sponsors can divide the participants into more manageable groups (such as eight or fewer candidates) with the candidate groupings decided by drawing lots or applying clear criteria. The multiple debates can be staged back-to-back or over several days; the Nigeria Election Debate Group (NEDG), for example, organized 12 presidential debates in 2007 so all 24 candidates could take part in pairs over the course of a day. For a 2013 governor debate in Anambra state, the NEDG invited some 23 candidates to take part. Although not all candidates ultimately participated, the NEDG held two debates per day for the candidates in groups of seven and nine respectively. A final debate was held with the top four contenders who were selected based on criteria, including a debate audience survey, the number of campaign rallies held and party structures. In Haiti, the Public Policy Intervention Group (Groupe d’Intervention en Affaires Publiques, GIAP) hosted 19 presidential candidates for the 2010 and 2011 elections. GIAP organized a series of five televised debates with groups of three to four debaters each over a five week period.

Organize Tiered Debates

Sponsors may wish to hold two debates, the first of which can include all candidates. The second would include just the front runners as determined by pre-established criteria.

Host Candidate Forums

Sponsors can offer all candidates the chance to take part in a public forum where each can briefly present his or her respective qualifications and platform in turn and potentially answer a few questions as time permits; such a forum could be held before the main debates involving a more limited number of candidates.

Provide Television, Radio or Print Media Spots

Each candidate can be invited to record an introductory media spot that can be broadcast to help gain public exposure; in Peru in 2006, for example, the debate sponsoring group Transparencia invited each of 20 candidates to record a 30-minute interview that was broadcast on state television in blocks.

Organize Both First Round and Run-Off Debates

In countries with a two-round election system, a debate sponsor can hold debates in a first round election with a large number of candidates and then stage a smaller event with the more limited number of candidates going to a run-off round; there is always the risk, however, that a candidate can win the election in the first round, making a second debate moot.

As noted, if a sponsor decides to limit the number of candidates in a debate, criteria can be set to determine who will be invited to take part. It may be useful to keep several principles in mind when establishing criteria:

Be Transparent

Global experience indicates that the most effective criteria are objective, impartial and easily understood by the general public. Announcing the criteria early in the election cycle — before candidates have been nominated — can help prevent later accusations of bias in deciding who will take part in debates.

Develop a Multi-faceted Set of Criteria

As noted, participation criteria can include a combination of factors, including constitutional and legal eligibility, an active party organization (including fielding candidates and presenting a platform, among others) and reaching a certain threshold in public support as measured by opinion polling. (See Example: Candidate Participation Criteria.)

Be Ready for Public Criticism

If some candidates are excluded because they or their parties do not meet pre-established criteria, debate sponsors can anticipate public complaints and even legal action from the affected candidates. Sponsors may wish to prepare for this scenario by proactively explaining the criteria publicly in advance and preparing fact sheets for possible questions from the media and candidates. (See Example: Reactions to Participation Criteria.)

Participation

Perhaps the greatest universal challenge that sponsors face regardless of country or culture is convincing candidates to take part in debates. (See Example: Candidates Reluctant to Debate.)

In the U.S., the reluctance of candidates to debate led to a 16-year gap between the landmark Nixon-Kennedy debates in 1960 and the Ford-Carter forums in 1976. By mitigating factors that candidates use to sidestep a debate and adopting strategies to build public support for debates, sponsors can improve the odds that reluctant debaters will make it onto the stage.

Understand Reasons for Reluctance

Candidates can be resistant to participating in a debate if they believe they have a commanding lead over opponents based on their analysis of the race or polling data. Debates can be seen as a gamble where a potential misstep could jeopardize their advantage. Incumbent candidates may also conclude that appearing side by side on stage elevates lesser known opponents by increasing their credibility and media exposure. Some candidates are disinclined to face opponents perceived as more able debaters, more telegenic or more fluent in the language in which the debate will be conducted. Moreover, debates can become part of the regular volleys between candidates in an election campaign, as they challenge or reject opponents’ calls to debate. If debates become perceived as a concession to an opposing camp, candidates may duck out for tactical reasons irrespective of the debates themselves. Moreover, how sponsors handle the many organizational aspects of a forum can be cited as reasons for evading debates. Although many of these factors are beyond the control of sponsors, understanding a candidate’s perspective and taking preemptive steps to accommodate where appropriate can increase the chances a candidate will take part.

Reasons candidates use to decline to debate include the following:

- Stated resons to decline to debate

- Dates of debates conflict with campaign events;

- Debate formats are deemed to be inappropriate;

- Debate venues, moderators or the media outlet broadcasting the debate are alleged to be biased in favor of other candidates;

- Incumbent candidates at their level of office “do not debate”;

- Debate organizers did not treat the candidate “respectfully”;

- Candidate prefers to dedicate campaign time to rallies or touring and meeting voters one on one;

- Debates are not part of the country’s culture;

- Date of debate conflicts with religious practices; and

- Not all candidates have been invited to debates; or conversely all candidates have been invited to debate.

- Unstated reasons to decline to debate

- Candidate is ahead in the race and does not want to risk his or her lead;

- Not confident in his or her ability to debate effectively;

- Unfamiliar with the concept of debates;

- Not comfortable speaking the language to be used for a debate; and

- Does not want to give his or her political adversary credibility by sharing the stage.

With few exceptions, most countries lack laws compelling candidates to take part in debates. (See page 51 for debate regulations.) Absent legal requirements, debate organizers can adopt strategies to help encourage candidates to take part.

Take Advantage of Political Opportunities

Although all elections can potentially provide opportunities to organize debates, races without an incumbent often offer particularly good prospects to go forward with forums and establish a debate tradition. Candidates are often on a more equal footing without the advantages of incumbency. They can also be more open to debates because of the potential media exposure and need to establish themselves with the electorate.

Generate Interest with Candidates, Parties and Opinion-makers

Before a campaign heats up, sponsors may find it helpful to meet with political party leaders and potential candidates to present plans for organizing debates. This respectful outreach can provide an opportunity to explain the benefits of debates and begin to establish the profile and professionalism of a debate group.

Benefits of debates for candidates and political parties include:

- Provide a unique opportunity to speak directly to voters without filtering by the media;

- Receive unparalleled media coverage that most candidates could not afford or may not have access to;

- Help rally party supporters by seeing their candidate in action;

- Reach more voters via a broadcast debate than they would through months of one on one outreach to voters;

- Connect with independent or undecided voters who are less likely to watch or attend a campaign rally than party faithful;

- Project a positive image of a transparent election and healthy democracy at home and abroad;

- Level the election playing field where one party dominates access to the media;

- Allow parties to showcase emerging leaders, such as women and youth, to revitalize the image of party and show inclusiveness; and

- Allow a candidate to raise his or her personal profile; even if a debater loses the election, the exposure can help with future runs for other and perhaps higher political offices.

Sponsors can sound out the candidates’ views on debates, which can be useful input for a debate plan. Sponsors can also seek out key media figures and respected opinion leaders (e.g., business and religious leaders) to discuss debate plans to gain their public backing, which can be helpful in convincing candidates to take part and generating public support. (See Tip: Use Editorials to Generate Support for Debates.)

The main means for encouraging candidates to take part in debates is to create a demand and expectation among the general public and opinion leaders for the forums.

Create Public Expectations for Debates

The main means for encouraging candidates to take part in debates is to create a demand and expectation among the general public and opinion leaders for the forums. To generate this support, debate sponsors can try to build interest as well as a sense of momentum and inevitability around debates. With each passing election and debate, this public expectation can grow until the candidates see skipping debates as too risky and the events become a regular part of elections. (See Tip: Use Media to Hold Candidates Accountable for Missing Debates.)

To help create public pressure, a debate sponsor can work with the media to generate a steady stream of news stories and editorials in favor of debates in the weeks and months leading up to the planned events. The different steps in organizing the debates and milestones in negotiations with candidates can also supply an ongoing series of media opportunities, including announcements and interviews on:

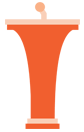

- Public opinion surveys showing that citizens support debates (see Data: Public Support for Debates);

- Debate initiative launch;

- Sites, dates and locations for debates;

- Formats;

- Topics; and

- Moderators and panelists

And as debate day gets closer, sponsors can begin to highlight the physical preparations via on-site media briefings to showcase the debate venue or set.

Select a Politically Significant Debate Location

Sponsors may wish to explore selecting a venue or location for the debate with political weight such as locales where candidates are vying for undecided voters, a must-win region, or a place of symbolic importance for historic or cultural reasons. All of these factors can enter into a candidate’s calculus on whether to debate.

Hold Debates for Different Levels of Office

If the concept of holding candidate debates is new to a country, it may be easier to start at lower levels of elected office, such as municipal posts. The political stakes are often reduced for parties, and candidates are frequently more apt to participate in debates. Lower level debates can also help establish the sponsor’s track record for impartiality and professionally organized events as well as generate public interest and enthusiasm for regular debates. Successful debates further show that the concept is not alien to the culture. Once introduced, the debate sponsor can move up the ladder of political offices to legislators, governors, or president or prime minister.

Negotations

In developing a plan to work with candidates on debates, sponsors may wish to keep several principles in mind to guide their approach as well as anticipate some common challenges.

Maintain Transparency and Impartiality

Above all, debate sponsors need to be seen as fair and impartial in their dealings with candidates and political parties. Allegations of political bias can be used by candidates as a reason to forgo debates. Once discussions on debate arrangements begin, it is important to provide candidates and their representatives with the same information at the same time. In this respect, it is recommended that as a general principle sponsors meet to discuss debates only when all candidates or parties are represented. Similarly, any information provided by the debate sponsor should be sent simultaneously to all candidates or parties to ensure transparency. (See Tip: Candidate Negotations.)

Develop a Debate Plan but Leave Room for Candidate Input

Before discussing debates with the candidates or their representatives, it is recommended to prepare a concise, easily understood initial proposal for the debates. By being proactive in presenting a plan, debate sponsors can demonstrate that they are capable and well organized— qualities that can increase candidates’ confidence that the debates will be professionally done. The plan can also help frame the debates discussion and hopefully help avoid arrangements that can undermine the credibility of the sponsor or make the debate less informative for voters. The plan can include such key elements as: the date, location, time, rules, topics and format. In developing a plan it is also helpful to identify the aspects of the debate that will be determined later by a coin toss such as stage position and who takes the first and last question, among others.

Frequent issues to be settled by a coin toss or by consensus with candidates:

- Time of candidate walk-through of debate stage;

- Arrival and departure times of the candidates from the debate hall;

- How candidates will be addressed (titles) by moderator;

- Stage position of each candidate;

- Which candidate makes first opening and closing statement; and

- Which candidate gets the first question and last question.

The plan should be clearly written and phrased so that it can be provided to candidates, parties and the media without concern. The items left to be negotiated with the candidates can vary from country to country and debate to debate. In some places, candidates have some degree of say over the selection of a moderator and panelists, particularly when a debate group is getting established. However, the long-term goal for the sponsor is to increase control of the debate arrangements incrementally over the course of each passing election cycle. In addition, organizers should think through their negotiating positions to identify the areas where they can be flexible and those where they should stand firm to protect the integrity of the debate or sponsoring organization. (See Tip: Candidate Negotations.)

Request a Candidate Representative with Final Say

At the outset of debate discussions with the candidates or political parties, it can be helpful to request that they name a representative who can make decisions on behalf of the candidate. A representative with this authority can help ensure that negotiations advance efficiently without having to pause to vet every decision. It can also be beneficial to have a representative, rather than the actual candidate, take part in negotiations. At times, the natural tensions among the competing candidates can make negotiations even more strained than necessary. It is helpful to have contact information to be able to reach the candidates’ representatives at any time to deal with unforeseen issues that come up.

Mark Milestones in the Negotiation Process

In countries where candidate debate negotiations stretch out over weeks or months, some sponsors have candidates’ representatives sign letters of agreement as different aspects of debates are settled. With concurrence from the candidates, these agreements can be shared with the public to help further commit the candidates and contribute to a sense of momentum toward debates by providing an opportunity for media coverage.

Plan for all Candidate Contingencies

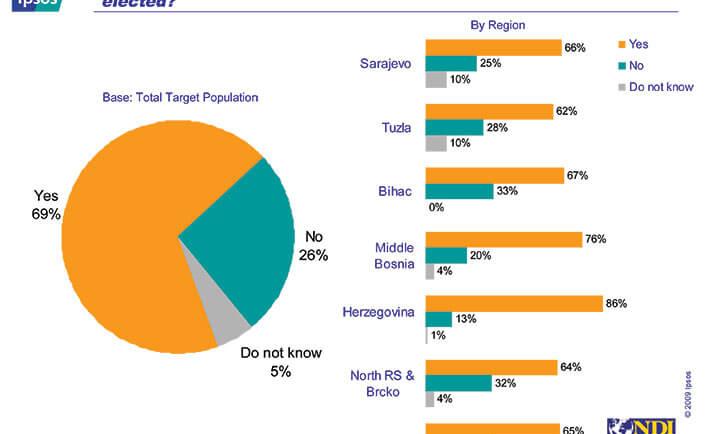

Sponsors may also want to think through all possible contingencies, including candidates declining in advance to take part or failing to show up the day of the debate. In these scenarios, sponsors are faced with the decision of how to handle the candidate’s absence. Depending on the country’s legal framework, relations with candidates and the political environment, debate organizers have explored different options for highlighting a candidate’s nonappearance. (See Example: “Empty Podium” Debate.)

If debate organizers choose to publicly highlight the absence of a candidate who refuses to debate by leaving their podium or chair vacant, they may wish to consider a range of issues as they decide which approach to take:

- How will the potential media attention of an absent candidate or political party affect the long-term relationship with the sponsor for future elections and debates?

- Are there legal media coverage requirements, such as equal time provisions, which come into play if a candidate drops out affecting whether the sponsor can proceed with the forum regardless?

- Were candidates informed in advance that their absence would be marked by an “empty podium”?

- Should sponsors make a distinction between candidates who formally declined a debate invitation in advance vs. those who agreed but do not show up at the last minute?

- Should a candidate’s absence be noted verbally by the moderator at the outset of a debate or highlighted through the event by displaying a vacant podium?

- If several candidates decline, will a large number of empty podiums on stage negatively detract from how the debate looks to the audience?

Media

Developing an effective partnership with the print and electronic media is essential to ensuring that a debate reaches the widest possible audience. The specific role of the media in organizing debates can vary according to the production arrangements (see page 30) and the composition of the debates sponsoring organization (see page 14).

Some debate groups have found it helpful to negotiate a cooperation agreement with media partners to ensure there is clarity on key aspects of the broadcast and what each will contribute to the debate effort. (See Example: Debate Sponsor–Media Agreements.)

Forming a partnership with the media can be affected by a range of issues that sponsors may want to anticipate and factor into their discussions. In some countries, as noted below, negotiations with the media have proved as challenging as the talks with the candidates.

Since candidate debates can clearly be historic news events, it can be beneficial to facilitate media coverage and avoid negative experiences that may color reporting of the debate itself.

Media Rivalry

Competition among media outlets may reduce their willingness to collaborate in a debate effort. This can include refusing to broadcast or cover a debate sponsored by a rival station. Sponsors may find it helpful to avoid this competition by working through media associations where all stations are represented or the state media outlet, which in some countries is not be viewed as a rival to commercial broadcasters.

Candidate–Media Tensions

Strained relations between candidates and the media over the tone of campaign coverage can lead candidates to “blackball” media outlets as debate carriers or specific journalists as debate moderators, running counter to station efforts to showcase their top on-air journalists. In some instances, this friction has led media outlets to threaten to boycott covering debates entirely. To help preempt such a situation, sponsors may wish to highlight publicly the criteria used to select moderators and panelists, and explain how the selection process is designed to respect both journalists and the debate.

Scheduling Conflicts

The media may also balk if the possible dates for the debates conflict with broadcasts that draw large audiences and generate significant advertising revenue. Consult with the media in advance to avoid this scenario. Sponsors of a 2014 provincial debate in Ontario, Canada, for example, had to work around a national hockey play-off game.5

Airtime Costs

The media may also request that sponsors pay for airtime for the debates, which significantly increases the fundraising burden on a debate group. Sponsors can make the case that free or discounted airtime is an important contribution to the public good and a civic responsibility.

Production

(see also Production Options in Production section)

Top quality production arrangements are central to ensuring that debates sound good on radio and appear professional and impartial to a live audience or people watching on TV. At a minimum, once a venue has been selected, a debate requires microphones and furniture for the candidates, panelists and moderator. If broadcast on TV, other elements will be required, including lighting, cameras and a set, among other items. If held outside a studio, a mobile production van may be needed to broadcast the event. Sponsors will also need production staff, which can be provided by a media partner or contracted. (See page 30 for a discussion of production considerations.)

Public Relations

Create a Public Relations Strategy

A key aspect of organizing a debate is facilitating media coverage of the preparations to build interest and support for the debate itself. This strategy can include such tasks as:

- Building a database of media contacts to be kept informed of the debate initiative;

- Developing press releases and fact sheets for regular media inquiries and interviews;

- Holding media conferences;

- Using social media to provide debate updates – homepage, Facebook, Twitter, etc.;

- Placing promotional spots on radio and television or ads in print media; and

- Drafting and encouraging allies to place pro-debate editorials.

Consider Special Arrangements for Working Media

Since candidate debates can clearly be historic news events, it can be beneficial to facilitate media coverage and avoid negative experiences that may color reporting of the debate itself. In some countries, debate sponsors elect to set up a work and hospitality area for print and electronic journalists at the debate site Although the size and services provided in this area can vary widely, the media should be able to watch the debate and file news stories. This area can be inside or close to the debate venue and can include seating and tables, TV sets, Internet and phone connections, electrical outlets as well as food and beverages. This space can also be used by the media to conduct interviews with candidates or their representatives after the debates. Some sponsors have opted to erect additional “stand-up” positions outside the debate venue. These exterior positions can provide locations for reporting before, during and after debates, including offering a telegenic backdrop of the debate hall and debate sponsor logos. (Example: Facilitating Media Coverage)

Establish a Web Presence

Sponsors may wish to set up a website and social media presence to serve as an information platform for the public and the media to promote the debates. In this respect, the site can include such information as:

- Debate organization mission statement;

- Leadership of the debate group;

- Date, location and time of the debates;

- Contact information;

- Press releases;

- Ongoing updates on topics, candidates, moderator or panelists;

- Information on debate tickets;

- News articles and pro-debate editorials;

- Ability to receive donations for the debates;

- Recognition of donors; and

- Web platform for live streaming the debate.

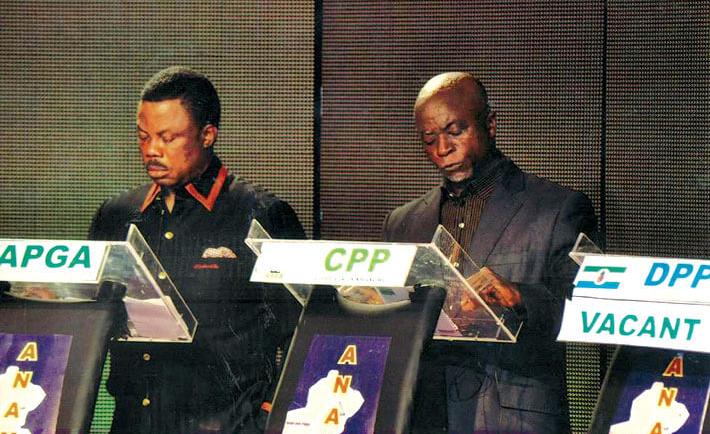

Create Printed Materials

As appropriate, sponsors may want to print tickets and programs to describe the debate and recognize donors. Posters may also be helpful to promote the event. (See Examples: Debate Invitation and Promotional Poster.)

Post the Video and Create Transcripts

To facilitate the work of journalists covering the debates, allow later viewing and help hold candidates accountable to their promises going forward, sponsors can post video of debates as well as transcripts as soon as feasible after the event.

Organize Voter Education Activities

Debate groups have developed many ways to multiply the impact of debates from debate viewing parties to online discussions, among others. (See page 48 for more information on debate-related voter education activities.)

Recognize Participating Candidates

To make debating a positive experience for candidates, some sponsors make it a practice to publicly present a certificate of participation at the conclusion of the forum. This recognition is designed to highlight the positive contribution that participating candidates have made by focusing the election campaign on issues, promoting civility and thereby strengthening democratic practices in the country.

- 1. Criteria based on discussions at the NDI and CPD sponsored International Debate Best Practices Symposium, Washington, D.C., June 2013.

- 2. Remarks at Los Debates Presidenciales en el mundo hosted by Argentina Debate, Universidad de Buenos Aires, October 30, 2014

- 3. Remarks at the Africa Debates Best Practices Symposium, Abuja, Nigeria, August 2013

- 4. Remarks at the NDI and CPD-sponsored International Debates Best Practices Symposium, Washington, D.C., June 2013

- 5. http://www.theglobeandmail.com/news/politics/ontario-leaders-debate-tentatively-set-fortuesday-june-3/article18707127/