Principles

Debates seek to help voters make some of the most important decisions affecting their daily lives — from choosing their mayor to president or prime minister. Because of the political stakes, the public and participating candidates will scrutinize all aspects of the debate production. It is important that production goes smoothly and avoids missteps that will “become the story” of the debates in the media rather than the content of the discussions. For these reasons, it is recommended to keep several principles in mind when producing the debate broadcast.

A Dignified and Respectful Event

The production values of the debates should reflect the significance of the decisions voters will be making at the ballot box for their local communities or country. As such, the set for the debate should be dignified and avoid the flashy, eye-catching production elements more appropriate for entertainment programs. A non-distracting, decorous backdrop helps keep the audience’s focus where it should be — on the candidates. A dignified setting further reassures candidates that they will be seen in a respectful and fair light, which can increase their confidence in the sponsor and encourage their participation.

The Debate is for the Public Watching and Listening at Home

If a debate is being broadcast, the viewing or listening audience will be far greater than those attending the event in person. For this reason, the debate should be produced primarily with the home audience in mind. This includes ensuring that the persons attending the debate do not divert the viewing or listening audience from focusing on what the candidates have to say. In many countries, the audience is asked to remain completely silent and may not be seen on camera beyond opening and closing shots.

Simpler is Better

While it may be enticing to add extra technology and production elements — such as exotic camera shots, elaborate backdrops, on-screen information (i.e. audience dial testing, etc.) — these additional features can add to the complexity of the debate production. Nonessential embellishments can also distract the audience’s attention from the candidates and consume a producer’s time and energy especially in the last days and hours before a debate. Although well-intentioned, additional features such as cellphone text voting (SMS) on the candidates’ performance or dial testing, among others, may be perceived as a sign of bias by some candidates and can discourage their participation in debates. (See Checklist: Debate Broadcast Equipment for basic production gear needed for a debate.)

Expect the Unexpected

Many a debate has been thrown off track by unforeseen, last minute technical problems. (See Example: Production Problems).

To avoid these potential snags, sponsors should consider having back-up systems in place for all key aspects of the broadcast and a contingency plan to deploy the appropriate equipment. First and foremost, sponsors should set up an independent power supply (i.e., generators) so that the debate can proceed regardless of disruptions in the main power source (i.e., the public power supply sometimes known as “shore power.”) Other back up items may include microphones for candidates, cameras, candidate timing clock, IFB earpieces, etc. It is recommended that back-up equipment be pre-positioned so it can be put into use with minimal interruption to the debate broadcast.

Moreover, debate preparations can go on until minutes before airtime. As candidates consider their own strategies, it is not uncommon for them to either fail to show up as promised or conversely to appear unannounced for a debate. These last minute changes may require adding or subtracting podiums and readjusting lighting and backdrops, among other tasks. Debate sponsors may wish to discuss and rehearse these possible scenarios so the production remains as seamless and professional as possible despite the inevitable bumps.

Whatever happens, don’t lose your sense of humor...

Marty Slutsky, executive producer, Commission on Presidential Debates (U.S.)

Create a Debate Production Schedule

As with other television productions, it can be helpful to create a detailed schedule that lists everything that has to be done for a debate right up until going on air. A schedule can lay out the timing, tasks, and responsible individuals to ensure nothing is forgotten. (See Example: Debate Day Production Schedule (Excerpt).)

Production Options

One of the benefits of candidate debates is that the forums can be widely broadcast on radio and TV, enabling the organizers to reach a wide audience. Ratings data from a range of countries show that debates can be historic events, often attracting a huge number of viewers or listeners rivaling or exceeding top entertainment or championship sporting events (see Data: Global TV Debate Audience).

In preparing to broadcast a debate, sponsors have a number of production approaches they can take — each with different budget and political considerations. It is important to weigh these tradeoffs in the context of each country and select the best-suited option.

Media Pool

With a “pool” approach, the majority of major television and radio stations work together to produce a single broadcast feed of the debate in collaboration with the debate sponsor. The cost of the production may be assumed collectively by the stations, reducing costs for a debate sponsor. The media pool may in turn provide or sell the broadcast at a reasonable charge to help defray the cost of production to non-participating stations. This approach reduces potential charges of political bias or favoritism since all stations are involved. Similarly, since all stations are engaged and providing support for debates, they are less likely to organize potentially competing events. The pool model can also contribute to making debates a national, historic event since all stations would broadcast the forum simultaneously. This approach is used by the U.S.-based Commission on Presidential Debates for general election debates.

Independent Production Company

Rather than relying on a media outlet partner, debate sponsors can contract with an independent company to produce the debates. This approach gives the sponsor more control of the set design and broadcast but adds the cost of covering all production expenses. It is important to select a production company that is perceived as politically neutral to avoid allegations of political bias that may affect how the debate sponsor is viewed. Although it varies by country, under this model, the debate sponsor may have to pay media outlets for the airtime to broadcast the debate. This approach is used by the Jamaica Debates Commission and the Trinidad and Tobago Debates Commission.1

Single Media Outlet

Debate sponsors can partner with the major state-owned media outlet and take advantage of the ability to reach a national audience and have production costs covered. The state media can in turn provide the broadcast feed to other stations at no charge. This model has been used in Ghana by the Institute of Economic Affairs and in Serbia by the Center for Free Elections and Democracy (Centar za Slobodne Izbore I Demokratiju, CeSID).2 Ideally, the state broadcaster is seen as a neutral entity. In some countries, however, the state media can be perceived as an arm of the incumbent government, which may have a candidate taking part in the debate. This can cause concerns that the debate broadcast will be biased in favor of the government candidate and make its competitors reluctant to take part. In response, in some cases, debate sponsors opt to show the debate live to mitigate candidate concerns about potential biased editing of the broadcast to benefit one camp. Another factor to consider is that some private stations may see the state entity as competition and reject broadcasting debates and instead air competing programming. This can also be the case if a sponsor selects a single commercial station, rather than the state media outlet, as a production partner since rival media outlets may reject broadcasting debates produced by a day to day competitor.

Combined Multi-Station “All Star” Team

To help give all interested media outlets a role — and a direct stake in producing the debates — a sponsor can ask the major media outlets to loan staff and equipment to produce the debate as an in-kind contribution. This option has the benefits of reducing production costs for the debate sponsor and encouraging the buy-in of all stations, which reduces the likelihood of a boycott by normally competing media outlets. A further incentive is to include major media reporters as panelists. One challenge is that the ad hoc production team may not have worked together, leading to a potential for production missteps, which can hopefully be avoided by careful planning and coordination. A variation on this approach is to work with several stations and have each broadcast one in a series of debates.

Whatever production approach is taken, it is important to determine who owns the legal rights to the final broadcast. This can affect the potential rebroadcasting of the debates or commercial use of the footage, including for campaign advertising. (Please see Box 10 for other issues to consider in a cooperation agreement with a media production partner.)

Production Elements

In planning for the debate broadcast, a range of tasks should be kept in mind, many of which have practical and budgetary impacts.

Debate Date

As noted, be sure to avoid date conflicts that can reduce viewership such as religious observances or popular sports and entertainment shows.

Venue

In selecting a debate venue with production considerations in mind, the simplest and easiest approach is to hold a debate in a television studio that has all the equipment in place. This is often a good option for a first time debate group. Alternatively, as noted, debates can also be held at other sites, including theaters, hotels or universities with the use of mobile broadcast equipment. (See Box 9 for recommended venue selection criteria.)

Broadcast

Debate sponsors around the globe have produced both live and taped forums depending on the local political environment, their production capacity and available resources. For the tradeoffs of both broadcast approaches, see Tip: Live or Taped Broadcast?

Stage and Set

The debate stage should accommodate a set that is comfortably sized for the expected number of candidates, moderator(s) and panelists. The height should be sufficient to fit theatrical lighting. The set itself should be dignified, neat, clean, not distracting and convey a sense of national unity. If debates are being held in different parts of the country, two sets may be needed if there is not enough time to transport them between events.

Make-Up

As with most television productions, it is recommended that the candidates, moderators and panelists have basic television style make-up. Make-up artists can be provided by the candidates or the debate sponsor. Candidates should arrive well in advance of the debate to allow time for make-up.

Venue Temperature

It is important to set a temperature that keeps the candidates comfortable and able to perform at their best. Sponsors should avoid unflattering TV images of candidates mopping their brows during the broadcast, which can be interpreted as signs of nervousness by the media or viewing audience. It is advised to focus particularly on the temperature on stage, which may be significantly hotter because of production lighting. If the debate hall is not air-conditioned, portable units can be positioned off-stage to help keep the candidates cool. Audience members will also appreciate a comfortable temperature setting.

Cameras

Ideally, sponsors should have a minimum of three cameras for candidates, panelists and the moderator. Cameras should be placed as close as possible to a head-on position for all the candidates. This positioning enables each candidate to look straight into the camera lens and therefore at the television audience at home. It also ensures that some candidates are not viewed at unflattering angles in comparison with their counterparts. The moderator and panelists should similarly have head-on cameras if possible. (See Example: Camera Diagram.)

Audio

Debate sponsors around the world have successfully used a variety of audio systems, including handheld microphones, lavaliers, fixed position and headset microphones for candidates, moderators and panelists. Each type of equipment has trade-offs. In general, lavalier microphones are recommended since they ensure audio will not be lost if a candidate turns away from the microphone. Lavalier microphones also leave a candidate’s hands free for gestures. Whatever system is used, however, redundancy is key. Have back-up microphones in place — e.g., candidates can wear two lavalier microphones or be provided with a back-up handheld microphone in case of technical problems. It is also advisable to have spare microphones pre-positioned in case of unexpected malfunctions.

Timekeepers and Timing Systems

Tracking the candidates’ speaking time is an essential aspect of ensuring fairness in a debate. Timing mistakes can lead to claims of bias by the debaters that can undercut the sponsor’s credibility and the willingness of candidates to take part. Since moderators and panelists will be busy with other aspects of the debate, it is advisable to task others with tracking the time used by candidates and questioners to ensure debate rules are followed. Debate sponsors have developed a range of creative approaches to let candidates and the audience know when time limits have been reached. These approaches include: hand held bells, pre-recorded sounds (from soft chimes to loud buzzers), “traffic lights” (green, amber and red lights), computer-driven countdown clocks, and colored placards (green, yellow and red) that can be held up for candidates and the live audience to see. Silent systems such as placards, traffic lights and countdown clocks have the advantage of enabling the candidates to monitor their time without the viewing or listening audience being distracted with audible reminders. (See Example: Debate Timing Systems.)

Timing systems can reduce the likelihood that the moderator will have to intervene and cut off candidates in mid-sentence when their time has expired, which can be perceived negatively or as a sign of bias. Whatever approach is employed, it is helpful to familiarize the candidates with the agreed upon time limits and the timekeeping systems to avoid on-air misunderstandings or mistakes.3 (Please see below for a discussion of candidate “walk-throughs.”)

Professional and Equitable Lighting

The quality of lighting can make a significant difference in how candidates appear on camera and to the debate audience. Uneven or poor lighting can make a debater look bad and open a sponsor up to allegations of bias by the candidates and the media. Care should be taken to provide adequate lighting and ensure the quality is the same for all candidates, moderators and panelists. It is recommended that the overall lighting not be overly dramatic so it does not distract from the candidates. A lighting check during a pre-debate walk through by a candidate (please see below) can provide an opportunity to tailor lighting to the candidates.4 A lighting director or camera person should be responsible for illuminating the debate set.

Audience

As noted on pages 19 and 29, having a live audience has many implications for debate preparations. On the production side, the additional persons at the venue can change the room temperature and generate noise during the broadcast. Sponsors may wish to use carpeting, drapes or other noise reduction materials to reduce ambient sound as well as have a moderator caution audience members as part of his or her opening remarks to be respectful and maintain decorum.

Translation

It may be necessary to provide translation as part of the debate broadcast or even for the candidates themselves. These arrangements should be part of the production planning process and may require additional audio equipment for the candidates, moderators, panelists and the broadcast. Some debate sponsors have also opted to include sign-language translation during the debates as a box that appears on screen, which may require an additional camera to film the interpreter and a digital video effects device to merge into the broadcast feed.

Candidate and Staff Walk-through

To help put the candidates at ease and contribute a polished debate broadcast, it can be helpful to invite debaters and their staffs to visit the debate venue a day or two before the forum when the set and broadcast equipment are in place. These visits — generally private one-on-one tours for each candidate or open time periods for multiple candidates — allow them to go on set and get comfortable with production arrangements such as testing the audio, learning which camera to look into and seeing where their holding room is located as well as where to enter and depart the debate hall. (See Tip: Importance of a Candidate Production Briefing.)

The tour can also provide an opportunity to review the debate format, including time limits for questions and answers and timekeeping systems, which can avoid confusion or missteps during the debates that can lead to candidate complaints. The visits are private working sessions and should be closed to media to allow the candidate to focus on his or her debate preparations and ask candid questions without risk of embarrassment.

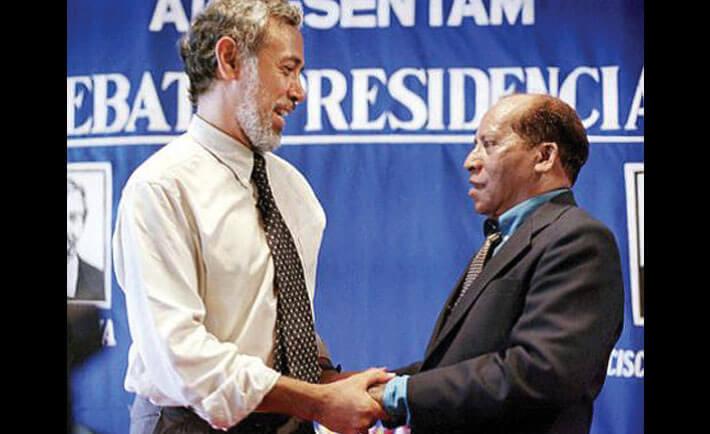

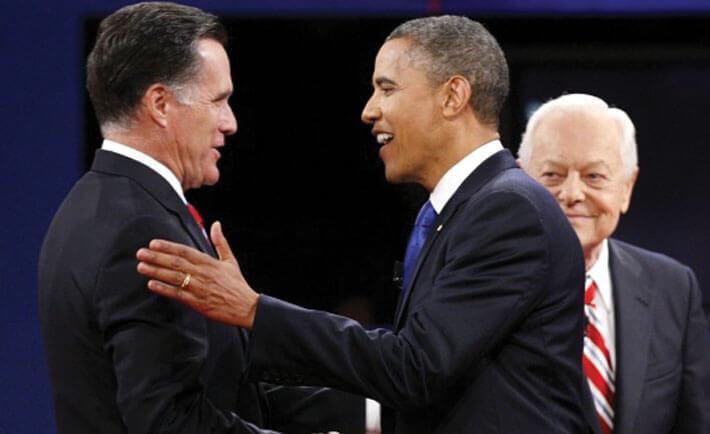

The “handshake” often becomes the lasting public image of a debate.

Organize “the Handshake”

One of the most important aspects of a debate is to show that despite their differences political opponents can discuss issues in a constructive, respectful manner. In this regard, the simple but symbolic act of candidates publicly shaking hands at the start and conclusion of a debate can have a powerful impact. The gesture sends a message of comity and national unity to all citizens, particularly in countries emerging from conflict or non-democratic rule (See Example: Candidate Handshakes.)

The “handshake” also often becomes the lasting public image of a debate. In addition, candidates in some countries have taken the opportunity of the closing handshake to jointly urge the public to refrain from violence and participate peacefully in elections. To ensure this moment happens, debate sponsors can take proactive steps. These include working out the handshake in advance with the production team and debaters and making the staging part of the walk-through briefing for the candidates (See page 38.) These preparations, which should include logistical arrangements for still photographers, can help make certain the handshake goes smoothly and is captured by the print and electronic media.

- 1. Jamaica Debates Commission (JDC); Trinidad and Tobago Debates Commission (TTDC).

- 2. Center for Free Elections and Democracy (Centar za Slobodne Izbore I Demokratiju, CeSID)

- 3. With the author’s permission, concepts and text in this section are directly drawn from the Commission on Presidential Debate’s Guide to Hosting Your Own Debate, CPD ©2012.

- 4. With the author’s permission, concepts and text in this section are directly drawn from the Commission on Presidential Debate’s Guide to Hosting Your Own Debate, CPD ©2012.